Back what seems like forever ago, I held a City of New Orleans Tour Guide license. A fellow Arkansas native named Finis Shelnutt dipped his toe into the “ghost tour” market, and made it a bit special because he allowed tourists into an ostensibly haunted building he owns in New Orleans. Some of you out there may recognize his name. He was married for a while to the Arkansas songbird of Bill Clinton fame, Gennifer Flowers. Gennifer wanted her own piano bar, and dutiful-husband Finis bought the building in which the club was to be located. According to Finis, the location’s history includes a Frank-Sanatra-only tribute club run by New Orleans legend Al Hirt, a down-and-dirty raucous club run by Humphrey Bogart’s mistress, Verita Thompson, and the totally-legal club that doubled as the parlour for the less-than-legal upstairs brothel run by madam Panama Hattie. And, as if all that weren’t weird enough, the building was once a home for children orphaned during the Civil War. Again, according to Finis, all the various entertainers and residents (including orphans and whores) remained in the building after their deaths, and only the select few of the living, who book his tours in advance, for a nominal fee, can experience this uniquely haunted mansion. As a tour guide working for Finis, it was my responsibility to retell all these “according to Finis” stories in gruesome detail, and to add in a few sightings and otherworldly experiences along the way.

While I love a good ghost story as much as anyone, I don’t do well just making stuff up. I became a tour guide for just that reason. New Orleans has so very much cool history, why do so many tour guides just make stuff up? In this vein, I took it upon myself to research this building and the people whose lives passed through it. And, boy, did I learn a lot. And, as you’ve already figured out, the truth is far more interesting than any exaggerated ghost story.

Meet Pierre Soulé. Pierre was born in 1801 in Castillon-en-Couserans, France. He was well educated, and as a youth, was quite outspoken against the French monarchy. While the Bourbons had been stripped of their divine right to the throne, a couple of times, Napoleon had appointed himself Emperor. To Pierre, nothing much had changed. The royal government considered young Pierre a royal pain in the ass, and in 1816 Pierre was exiled to the independent state of Navarre. After a short time, he was allowed to return to his native land, and once there, he wasted no time in restarting his revolutionary activities. While he was practicing law in Paris, the French government snatched him up again. But this time, the punishment was much more severe. Pierre Soulé was sent to prison.

Although Pierre was sentenced for only three years, it must’ve felt like a lifetime for such a young man. He did the only thing he knew to do; he escaped! He fled France, an escaped convict on the run. He stopped for a very short time in England, then moved right along to the island of Saint-Domingue and its French-speaking colony that is now Haiti. From there, you guessed it, he made his way to New Orleans. Remember Louisiana was heavily influenced by French settlers, and at the time of Soulé’s arrival, the City of New Orleans was still very much a French city. But that unique city was also very American. The Revolutionary War (which must have delighted young Pierre to his very soul) was less than fifty years earlier. The Louisiana Purchase, which secured New Orleans as a part of this new country, was only twenty-two years before his arrival. What a dream come true! He was surrounded by his countrymen, able to speak his native language, but was free from the government he despised and surrounded by men who believed in rule by the people. Pierre Soulé was home.

As one does, Soulé set about the business of living life. He married, fathered children, became a naturalized citizen of the United States, practiced law, and even founded a bank. For our story today, the most important thing he did was build his home at what is now 720 St. Louis Street. Construction began in 1829, when Soulé was only twenty-eight years old.

With the failure of his bank after the Panic of 1837, Soulé lost a little faith in his national leaders. While President Andrew Jackson’s hatred of the national bank & his distribution of funds to small “pet banks” were not the only causes of the nationwide economic depression, those actions left a bad taste in the mouths of many Jackson supporters. Then when Jackson’s friend and successor, President Martin Van Buren, did nothing to right the ship, even more regular Americans felt the pinch and blamed their federal executive branch. Soulé’s response was to throw himself into politics at home. He joined the Democratic party and served as a delegate at the state’s 1844 constitutional convention. In 1846, he was elected to the Louisiana State Senate, and in 1847 he was appointed by the Louisiana legislature to serve the final two months of a vacated seat in the United States Senate. Later, in 1849 he ran for and was elected to his own U. S. Senate seat. An historical event of note while Soulé was serving as Senator: Solomon Northup’s kidnapping and sale into slavery was a hot topic in Washington, D. C. The kidnapping had actually occurred in D. C. in 1841 while Northup, a free man from New York, was performing music there. Only after Canadian Samuel Bass took word of Northup’s forced servitude back to New York was action was taken to release him. Even though D. C. was still a slave-holding city and absolutely nothing was done to punish the kidnapper(s) there, Pierre Soulé and a few other Senators risked their personal reputations to give aid and support to Bass and others involved in righting this incredible wrong.

In April, 1853 Soulé resigned his Senate seat to accept the appointment as United States Minister to Spain. It was in this capacity, as a representative of the United States acting under the direct authority of President Franklin Pierce and Secretary of State William Marcy, Soulé was expected to secure the purchase of Cuba from Spain. A note of context here: The precedent of acquiring Spanish colonies had been established with the Onis-Adams treaty in 1821, by which the young United States of America acquired the Spanish colony of Florida. But Soulé failed to negotiate the deal. A short time later, in October, 1854 Secretary of State Marcy directed U. S. Minister to Great Britain, James Buchannan, and U. S. Minister to France, John Mason, to join Soulé in Ostend, Belgium. In what would later be called “The Ostend Manifesto,” the three men used what has been called “intemperate” language calling for the seizure of Cuba by force. Soulé‘s undoing was simple. The existing labor force in Cuba included slaves. Therefore, Cuba could be admitted as a slave state within the guidelines of the new Kansas-Nebraska Act (which allowed entering states to choose). Therefore, Soulé must be pro-slavery. Even though the Manifesto was never acted upon, when news of its contents leaked over a year later, the Republicans and abolitionists across the country were outraged. They perceived the acquisition of Cuba as cheating somehow, because of a law they already didn’t like anyway. Forget that Franklin Pierce had already authorized the peaceful acquisition of Cuba, and the key difference proposed in Ostend was to acquire Cuba by force. The opposition now had Soulé‘s number, and Soulé had no idea how much that meeting in Ostend would change his life.

For all his words to the contrary in the Ostend Manifesto, Pierre Soulé was otherwise not actively pro-slavery, nor did he actively support southern succession. At the 1860 Democratic National Convention, he strongly supported presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas and the Unionist contingent within the Democratic party. He was actively against secessionist delegates. After Douglas secured the nomination, Soulé went on to actively campaign for him in the 1860 presidential election. (Flashback here: While serving in the Senate in 1854, Douglas introduced the bill that would become the Kansas-Nebraska Act – the very law that caused Soulé so much trouble regarding the acquisition of Cuba.) However, once the war began in 1861, Soulé acquiesced. He supported his adopted home state of Louisiana in its succession from the Union and embraced its position as a new state in the Confederacy.

In 1861, Pierre Soulé was captured by federal troops, charged with treason for his alleged pro-slavery, anti-Union opinions, and imprisoned in Massachusetts. He did the only thing he knew to do; he escaped! He lived in relative anonymity somewhere in the South, but he no longer had a home to return to in New Orleans. The Soulé Mansion, his home since 1829, was now the property of a traitor to the Union and, as such, was seized by the federal government.

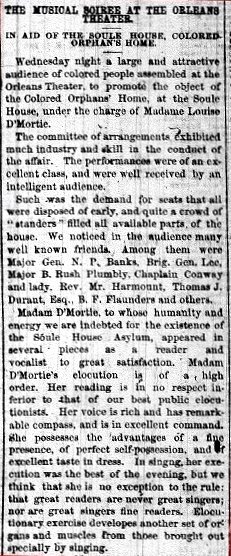

Enter Louise de Mortie. Louise was a free woman of color who fancied herself a performer. What she lacked in singing and acting talent, she more than made up for in enthusiasm for her latest cause: providing shelter for children orphaned by the fighting. This is quite peculiar. No shot was ever fired in New Orleans, as the Union occupied the city from almost the beginning of the war. Many free people of color already lived in New Orleans, and many had family roots almost as far back as the City’s inception, some 140 years before. So-called orphan asylums in New Orleans were numerous during this period in the City’s history, so much so that the state conducted an inquiry into the well-being of the “inmates” housed in at least ten of these orphanages. So, who exactly were these orphans, and why was Louise compelled to shelter them? As it turns out, Louise had a kind and generous heart, but Louise wanted the building, and Louise wanted the attention. She ensconced herself in the ground floor and created a showplace for her performances. She hosted charity events, for her very own charity, at which her poetry reading and singing were the sole entertainment. And the people of New Orleans came. And the people of New Orleans supported her. And the people of New Orleans loved her. And, hey! what better place to house poor orphaned children of color than the very home of that awful traitor, Pierre Soulé.

In the meantime, Soulé was again an escaped convict, on the run, but the everyday challenges of sustaining such a brutal and bloody war meant that nobody in the Union was really looking for him.

Fast forward in our story a bit, to 1865. The war was over and the Confederacy was destroyed. Pierre Soulé was in self-imposed exile in Havana, in the very country he wanted to bring into the national fold just eleven years earlier. Historical records are lost or incomplete, but it appears that only a few orphans remained in residence at the Soulé Mansion in 1865, and within a year, the house was closed. Louise de Mortie had made her home there in that house, and in 1867 after contracting yellow fever, she passed away there. She was only thirty-three.

In an incredibly interesting nugget of irony, in 1868, then Secretary of State William Seward wrote letters to President Andrew Johnson and several United States Senators requesting that Pierre Soulé be pardoned and given back his home. Seward was an abolitionist before the War, a Unionist during the War, and an additional target for assassination by the conspiracy that murdered President Lincoln. Seward was an incredibly interesting character on his own, and the folds and twists in his story are worthy of additional research. As for the Soulé Mansion, who knows what might have happened had Seward’s not intervened. As it was, Pierre Soulé’s home at 720 St. Louis Street in New Orleans was returned to him, and he died there, in his bed chamber on the third floor, in 1870.

So, here’s to the ghosts of the Soulé Mansion. I hope the stories are true. I love the idea that this interesting French native and American politician shares his giant home with Louise de Mortie. I love the idea that orphaned children of color and prostitutes are hanging out together for eternity. I love the idea that Al Hirt and Verita Thompson are telling Pierre Soulé of the New Orleans of their time. They should all feel right at home. Much of the opulence of the original building remains or has been restored, thanks to its current owner, caretaker, full-time resident, and ghost-storyteller Finis Shelnutt. Here’s hoping that in the next two hundred years of this building’s history, Pierre Soulé’s incredible story isn’t lost, and his ghost welcomes the spirits of his mansion’s current resident and all its future residents. Maybe future visitors to this incredible building will hear Gennifer Flowers and Louise de Mortie belt out a ghostly duet. And maybe, just maybe, they’ll even hear a few ghastly ghost stories from a departed tour guide or two.